When I studied music composition at the University of California in the 2000s, a new wave of contemporary classical music was on the rise. Max Richter and Jón Þór “Jónsi” Birgisson were at the crest of this wave, and I could sense the students around me wrestling with the influence of their sweeping, minimalist atmospheres. For us, this music created a fresh, liminal space between the atonal music of the academy and the ambient experiments of post-rock.

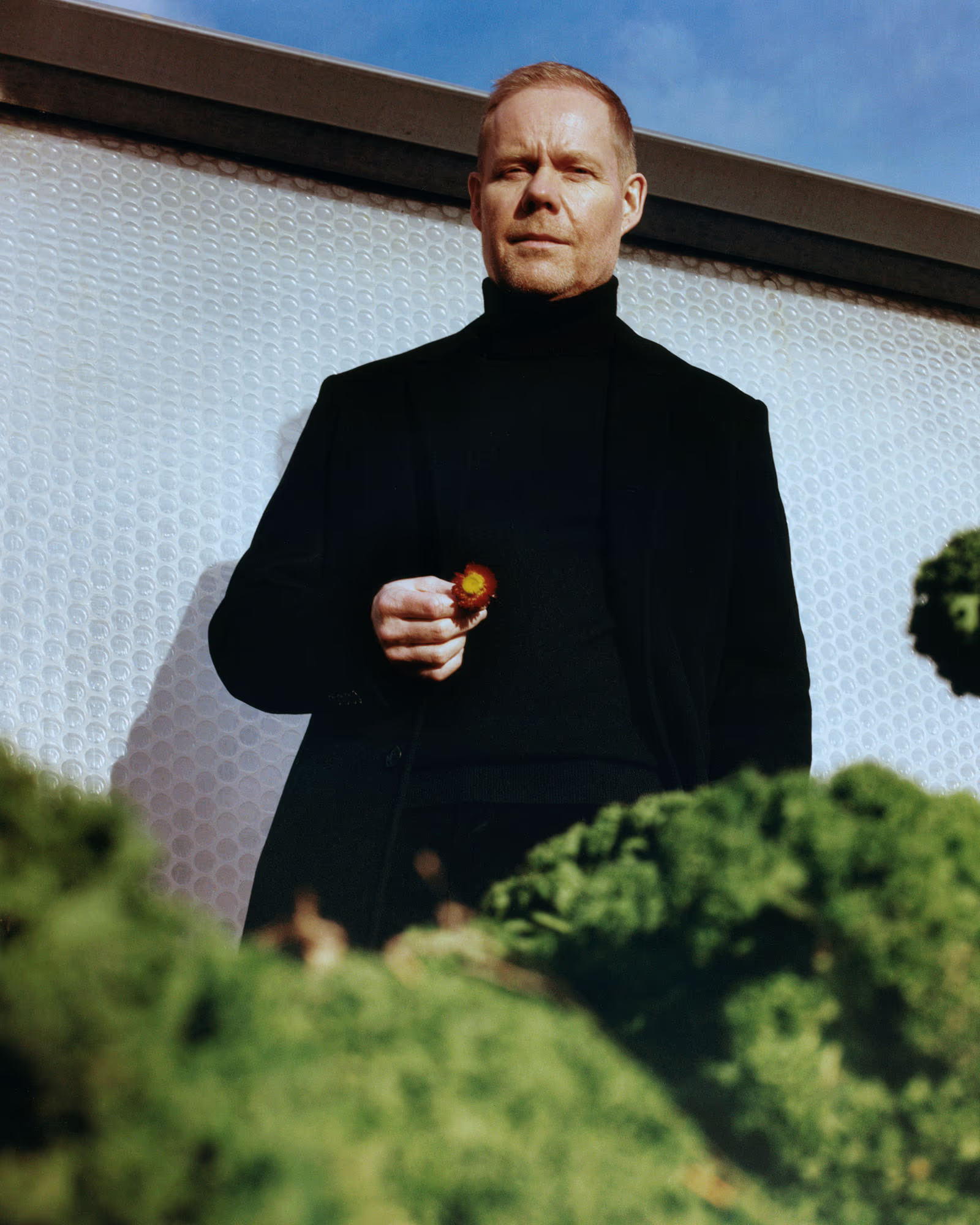

Richter’s first album in 2002, Memoryhouse, is a grand gesture that folds together electronics, field recordings, and orchestral music into a portrait of war-torn Europe. Since its release, he has played with many modes of composition: rewriting the music of Antonio Vivaldi, scoring dozens of films—Ad Astra (2019), Spaceman (2024), and my personal favorite, Never Look Away (2018). In 2015, he released Sleep, an eight-and-a-half-hour album that serves as a soundtrack to a full night’s rest. It has become the most streamed classical record of all time.

While Richter was composing Memoryhouse, Jónsi was emerging as the guitarist and singer of Sigur Rós. He became iconic for his technique of “bowing” the electric guitar and singing in a nonlinguistic glossolalia he called “Hopelandic.” Alongside his work with the Icelandic post-rock band, he has released solo albums, film scores, and sound installations, which hum from sculptural swarms of speakers. Now, he’s preparing for the band’s next tour, which will be accompanied by a chamber orchestra.

Both artists have opened doors for a new generation of composers—Nico Muhly, Julianna Barwick, Nils Frahm—and with every project, their experiments continue.

Max Richter: I really like the idea of music having a utility, a kind of a function. There’s something very human about the relationship we can have with it: Music has a different space in your life. When I made Sleep, it was blasphemous. From a classical music point of view, you’re supposed to sit down, behave yourself, and listen. I wanted to make this piece that was not really about that—a piece that was like a tool for somebody to use, like a mini pause button. Or a big pause button. Something that could be useful in somebody’s life, a conversational relationship with the listener. I enjoy that. Classical music has this weird idea that the composer is supposed to be some kind of godlike genius who delivers this text, and then you’re supposed to absorb it, or try to. I wanted to flatten that. I wanted to equalize that so the piece of music becomes a shared space and, in the case of Sleep, a direct utility.

Jónsi: I have a hard time grasping this word—functional. I just never really think about function. I always just write music for myself. In theory, when I do music it’s very self-serving, and I never think about anything or anybody or how they would like it or how they listen or what they do. Everything is just egotistical. I’m an egomaniac.

MR: I do think that there’s a dimension of creative work that is to support your ego. But I would say that there is also a dimension that is about constructing a world, right? Part of what you are doing when you’re writing a piece of music is proposing a kind of a reality. It’s a sort of like, What if the world was like this? And that’s mostly to do with a feeling of dissatisfaction with the actual world. If we were delighted by the actual world all the time, then we probably wouldn’t do very much creative work. In creative work, there’s an element of critique of the reality that we find ourselves in. I think that’s quite natural. I’m interested in what each person brings: their biography, everything they’ve heard, everything that’s happened to them. They’re meeting that piece of music with all of that, and that’s as interesting as the piece of music, right? Then you get this alchemy between these two things. There’s some vocal music in Sleep, and when I first talked to people about it, they had all different ideas of what it actually was. There was a Scottish journalist who went, “Oh, it’s a Celtic lullaby.” My A&R guy at Deutsche Grammophon said, “Oh, it’s a fugue subject.” Someone else told me it sounded like Enya. It was really striking that everyone was imprinting this with their ideas. One of the beautiful things about creative work is that it has this multidimensional possibility—and that’s to do with who’s listening.

J: That’s a pretty good compliment. I used to listen to Enya when I was around 17. Now people are starting to listen to her again. She’s such a fucking genius. Beautiful, incredible layers of vocals. Amazing songwriting. Really cheesy synthesizers. She never tours, never plays live but has sold millions of albums.

MR: What she was doing at that time was not easy, without Pro Tools or whatever. It takes a really high level of skill and time to achieve that.

J: I really relate to that. The harmonizing of vocals is so fun. When I’m in the studio singing, I sing once and then another three, four hundred times. Then I sing harmony to that and sing more. It’s so fun to hear those layers stack up. I have a love-hate relationship with listening to music. I just get enough when I write or when I am in the studio doing something. When I come home, I just want to have silence, or I put on a lot of nature sounds. There’s one artist I’ve been listening to, Aho Ssan, who is incredible. It’s the coolest soundscape I’ve heard in the last 10 years. It’s pure texture, distortion, really granular and intense. I don’t drive a lot, but when I do, that’s the only time I actually listen to music because it’s such a private thing.

MR: The car is a really nice way to listen to music. I’ve just finished 20 years of school runs with my three kids. We live basically in the middle of the woods, so a big part of my driving has been the school runs, and there was always music. With my daughter, we basically negotiate—I’m allowed my stuff on the way in, and she’s allowed her stuff on the way home. My go-tos are normally sort of old dub. You know, Studio One, King Tubby. I love that stuff. But she’s obviously, as a teenager, into songwriters. She turned me on to Mitski originally, who I love. It’s a good way to hear stuff you weren’t expecting.

J: I heard this really good story about Brian Wilson—he had to stop his car when he heard the Ronettes. At that time, that production was amazing. It still is.

MR: They’re amazing records.

“Classical music has this weird idea that the composer is supposed to be some kind of godlike genius who delivers this text, and then you're supposed to absorb it, or try to. I wanted to flatten that.”

— Max Richter

J: I do a lot of perfumery; it’s my big passion. I have a lab downstairs in my basement in LA. I have thousands of bottles of aroma molecules and essential oils. I’ve been doing it for like 15 years now. It’s so hard to describe scent. It’s so hard to write about it. Like there’s no words for different senses of smell, and it’s kind of one of the only senses that goes instinctually right in your brain with no defense. It’s actually a little bit similar to music. They’re both invisible and move you, and it’s instinctual—you have no idea why or how, which is kind of amazing.

MR: Like music, it goes to the oldest part of the brain. It can bypass the frontal lobe. Right in the feels.

J: My three sisters and I run a perfumery in Reykjavík, so we also do scented concerts, and we just did a big exhibition in the National Nordic Museum in Seattle. I’m also doing some art shows next year. Some installation stuff. Then I’m going on tour with Sigur Rós again. It’s two weeks with an orchestra. I’ve never done that before.

MR: I’m touring as well. I’m going to Australia and then over to the States. It’s me, a piano, a bunch of electro stuff, and five strings. Now I’m working with Chloé Zhao on Hamnet, starring Paul Mescal and Jessie Buckley, based on the book of the same name by Maggie O’Farrell. Chloé is a wonderful, interesting director. She made this film Nomadland [2020]. We are deep in the process of her new movie. I’m having a lot of fun with that.

J: Also, you did Spaceman with Johan Renck, right?

MR: Yeah! I have a lot of fun working with directors. We’re basically storytelling creatures, and music is one way to do that. A lot of my work has been either responses to literature or involved with text and words. It’s about literature, for me. I love reading. I love poetry. I’m reading the new [Haruki] Murakami book. It’s called The City and Its Uncertain Walls [2023]. He’s an interesting writer because he basically just writes the same novel over and over, but I’m fine with that. I love this feeling of somebody going deeper into their work. There’s a lovely Zen story: A student says, “Please show me Buddha nature.” And the master holds up a little tile and starts polishing it. I think that’s what Murakami is doing. He’s just polishing that tile. Why not?

All the books we’ve read, the music we’ve heard, the things we’re interested in lead to a fingerprint. And I think there’s something quite beautiful about somebody having a fingerprint. But within that, a lot of what I’m doing is in response to something. A lot of the records have sort of sociopolitical dimensions or stories I want to tell. But at the same time, it is just me writing. So both those things have to be in balance. There’s nothing nicer than hearing the first note of somebody’s record and going, “Ah, it’s them.”

J: True. That’s like your voice. Like you said, we all have our own way of working, and we start from some kind of place that we are comfortable with. I’m always searching. Guitar is my main instrument, but I’m so tired of it. When I do music for my art, I always start with my voice, and a very natural flow point comes through me. It’s instinctual, maybe like you writing on the piano. You don’t have to think; things flow through you, and that’s a very good point to start.

MR: That principle of searching that you mentioned is really fundamental, isn’t it? You basically start out with a whole bunch of stuff you don’t know. And that’s what’s interesting, right? You move into a space of things you don’t know, but it’s still you.

Grooming PAUL DONOVAN.