At nearly 80, Vera Tamari is a doyenne of the Palestinian art world. Born in Jerusalem in 1945, she studied fine art at the Beirut College for Women (today’s Lebanese American University), ceramics at Italy’s National Institute of Art in Florence, and Islamic art and architecture at Oxford University in England. Despite Tamari’s travels, she has always returned home to Palestine. “I always felt linked,” she says. “Not like a heroine, but I have a big cause to come back to.”

Tamari’s work ranges in material, theme, and scale, from bas-relief clay dioramas, inspired by family photographs that forms the basis of her memoiristic 2021 book Returning: Palestinian Family Memories in Clay Reliefs, Photographs and Text, to massive and conceptual, including the installation Going for a Ride?, 2002. Such combinations of intimacy and abstraction—often ironic—defamiliarize themes of memory, tradition, and injustice while inspiring curiosity.

I didn’t know about Tamari until recent events prompted me to learn more about Palestinian art. My conversations with her aided this effort: Tamari’s personal experience as an artist in Palestine offers an oral history of some of the region’s biggest art movements of the last 50 years. She delivers it with casual lucidity, aided no doubt by her many years as a professor of art history and visual communication at Birzeit University in the West Bank, where she founded the Ethnographic and Art Museum, and within it, the Virtual Gallery, an online space to facilitate cultural exchange between artists within Palestine and those beyond. Started in 2005, it’s currently defunct due to lack of funding but remains a valuable archive and a testament to Tamari’s vision and resourcefulness. I ask her if she thinks it might someday be resurrected. “I always hope it will,” she says.

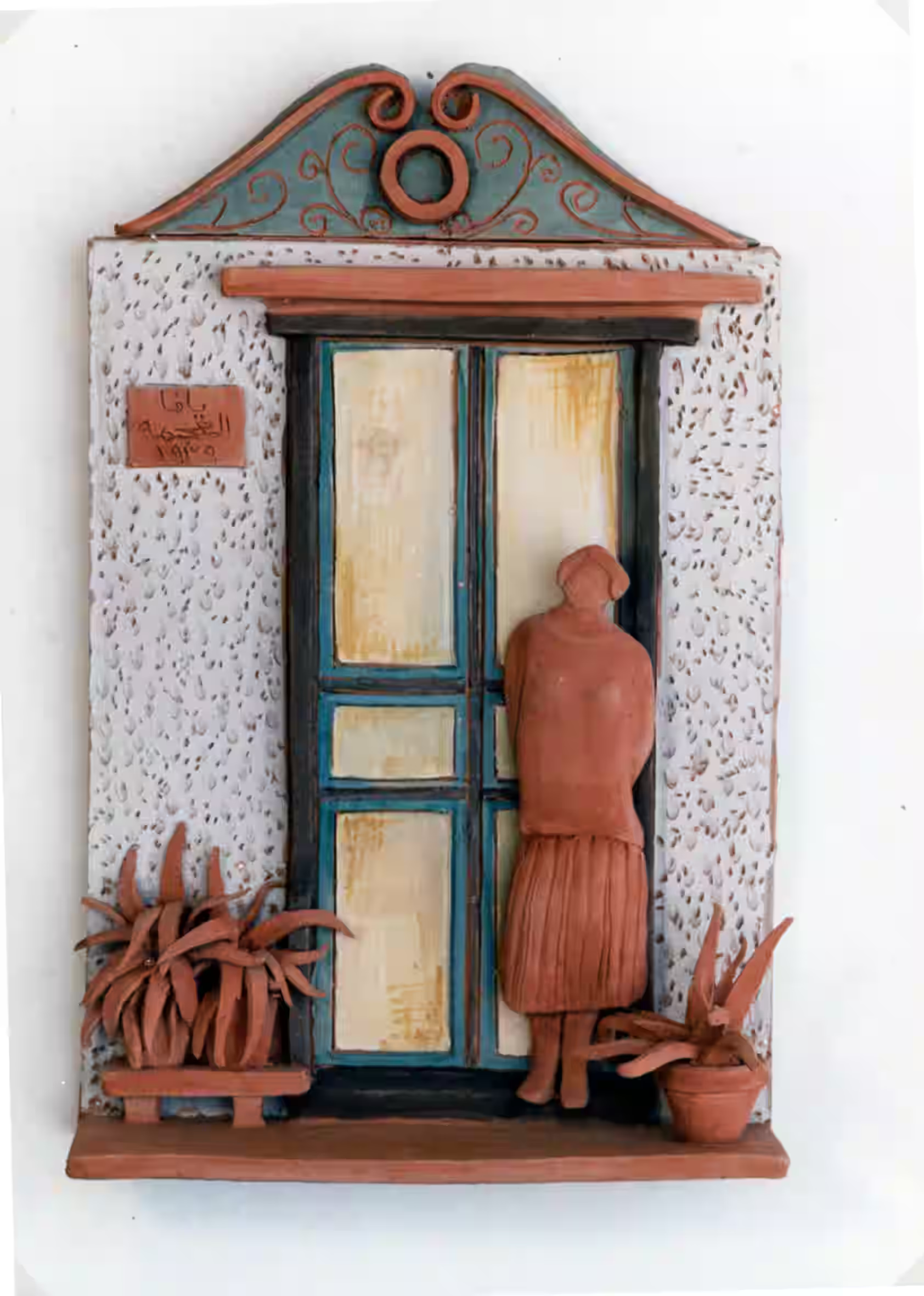

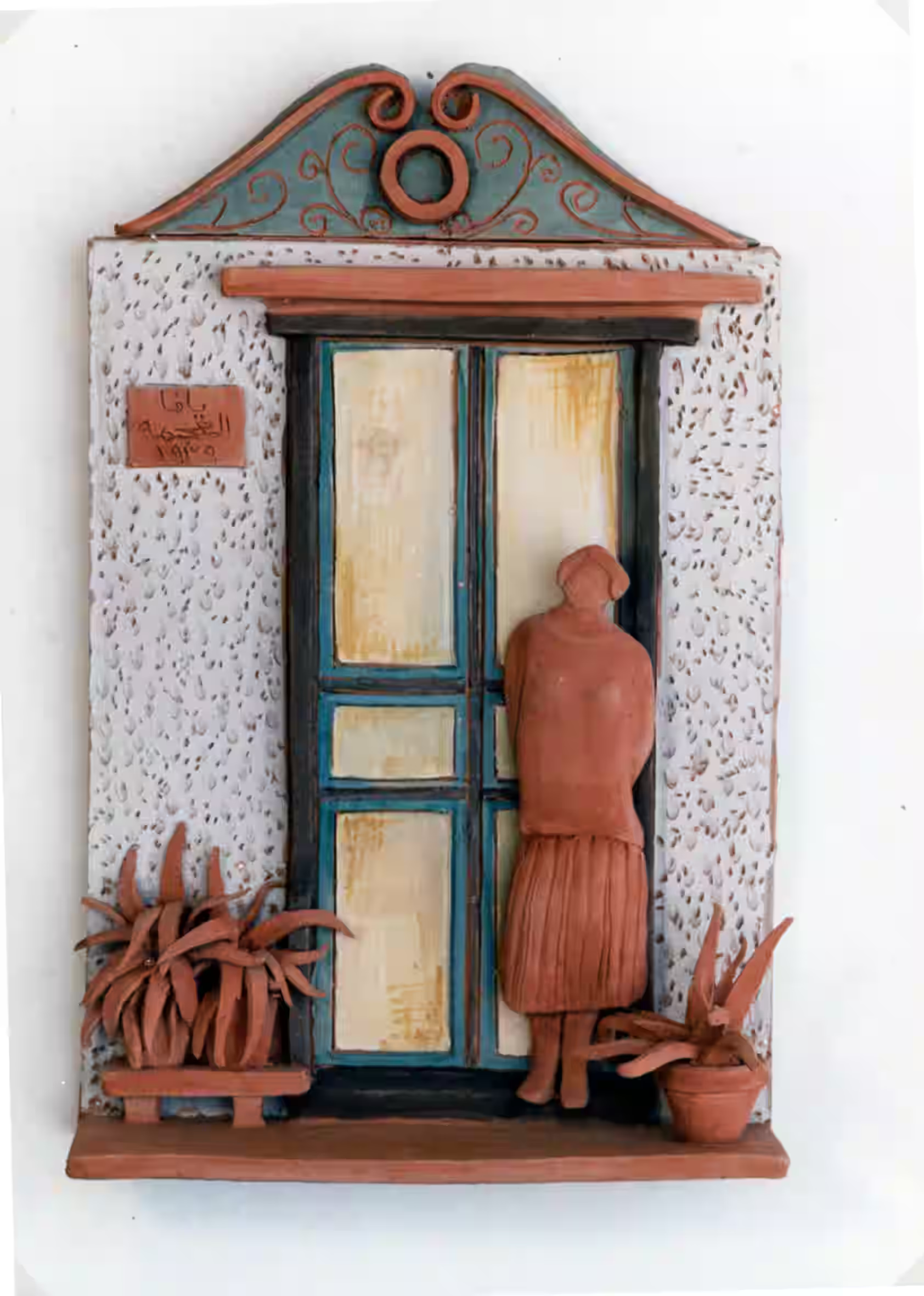

Vera Tamari, Woman at the Door, 1992. Image courtesy of the artist.

Rose Courteau: Where are you right now?

Vera Tamari: Ramallah. It is about 20 kilometers from Jerusalem, but to get to Jerusalem takes us a whole day, because we're not allowed to go as Palestinians. There are big checkpoints. You need a permit and stuff like that. It’s a big hassle and humiliation. I haven't been in Jerusalem in five years. The whole situation in the West Bank is so very low, depressed, and sad. We're just onlookers. I know some of the artists [in Gaza]. They have no food, no water. We live in one world, imagining how we can help them survive as artists, but they want to survive as human beings.

RC: I agree, there's something that feels farcical about a conversation about art right now.

VT: And yet it’s good! Through my book, Returning, I was able to talk about the Palestinian plight since 1948 and before the Nakba, and how Palestinians were living in cities like Jaffa and Jerusalem. Because I was very small when the Nakba took place— maybe two and a half—and I don't remember anything, it was important for me to put myself in through photographs [and] stories from my parents, who talked about the people in the pictures—the aunts, uncles, cousins, my mother. I'd like to talk about The Woman at the Door.

RC: Let me pull it up.

VT: The Woman at the Door is my mother. It was one of the first [of the ceramic “Returning” series]. My mother was very special. She was highly educated and very sensitive. [In the photo] she looks full of anticipation. After I did the relief work, I found a little amulet of hers in which she had folded paper from her diary. It was from the day before her wedding in 1940. She wrote about how she served her last night in bed in her own house in Jaffa. She said, “I don't know what the future will be.” My father was a collector of images and used to take family photographs. We were fortunate as a family to have kept these photographs, and I was lucky to be able to reconstruct some of the stories that I heard from them.

Marguerite Nicola Debbas, taken 1939. Image courtesy of the artist.

RC: Who took the photo of your mother?

VT: I don't know. I don't think it was my father, maybe.

RC: How long did it take you to make this work?

VT: I don't remember. Making it was very emotional. I felt very linked to the people and setting. Each relief probably went quite fast because I was enjoying them so much. I didn't do the whole series in one go. I did it over years.

RC: One thing I love about The Woman at the Door is her jaunty posture and the way that you managed to convey this sort of relaxed expectation with just a little bit of clay.

VT: That's what I felt. I'm not trained as a painter, but when doing these figures, I felt immediately the shape, the attitude came out naturally without fussing too much. The position, the postures, the different little daily gestures just struck me—how I was part of it.

RC: Would you like to talk about Home, 2017?

VT: It's completely different. Home is installed in the garden of the Palestinian Museum [in Birzeit]. I was commissioned [by the museum] to do a work on Jerusalem. Palestinians lived there for centuries. I made these steps [of Home] in the open, but caged. It's symbolic of being inaccessible. I had an opening in the top where the steps went up, towards freedom, eventually hoping that there will be access.

RC: What are the materials? How long did it take you to make?

VT: The steps are green plexiglass. Wire mesh is surrounding it. The design and planning took a long time, but the execution went very quickly because the technician with whom I worked was amazing. There was no light in the garden [when it was installed]. They had little torch lights, and I was watching them and telling them, “Oh, be careful, not that one!” But it's still there, and it's lovely because it’s surrounded by a lot of the natural landscape in the garden of the museum. Each season, flowers and plants grow around it. Sometimes in winter it becomes dull. Sometimes there are clouds, sometimes it's bright blue skies. The axis of the cube is in the direction of Jerusalem itself. That was very meaningful for me.

RC: I'd love to hear more about your different eras of artistic practice and how those have evolved.

VT: I started doing art in the ‘70s when there was a huge movement by the League of Palestinian Artists to do political art. A lot of imagery came out, especially in paintings, connected with issues of occupation and freedom: the symbol of the dome of the rock in Jerusalem, of the shackled prisoners breaking their iron, the land. I couldn't get too engrossed in the symbolism, so I shifted to studying Palestinian village life in the clay reliefs I did, to document and record the Palestinian women's embroidered dress, the crafts that they made. In the late 1980s, me and three other prominent artists [Nabil Anani, Sliman Mansour, and Tayseer Barakat] felt that everybody using the same symbols was repetitive. We started a group called New Visions. Rather than painting with oils, they would use mud and natural things. For me, it was also a shift in subject matter towards the person and the family through the family portrait. Then it happened that installation art started to infiltrate our way of reading. We had encounters with Mona Hatoum. She came here and talked about how conceptual art can address issues the indirect way. Going for a Ride, 2002 was partly [produced] because I had this background as a theater person. But I continued using clay within a bigger concept.

RC: When were you involved with theater?

VT: I studied drama as a minor in college. I liked directing and stage design. I was involved with a theater group in the ‘70s here in Palestine. We were all amateurs. There wasn't any theater, so this was just a very experimental group. I was in my early thirties, something like that.

RC: Where would you put on the plays?

VT: In schools or municipality halls. I remember one major thing we did in an unbuilt municipality. It was only the skeleton of the [building]. We brought in little chairs and there was no electricity, but the whole play was all based on that. We used candles.

RC: How have the political and material circumstances in Palestine influenced your art or the art scene there more generally?

VT: It's a big question. We started doing art without having colleges and museums and galleries in Palestine to support the art that was being produced. Most artists had studied abroad, either in Iraq or in Egypt or in Syria, and came back with foundations of art that were common in those [areas], especially in Iraq. This Russian socialist movement was affecting the style of painting, all very classical and well-studied. Because we didn't have art schools or museums, the visual background of the audience was limited. When they saw these paintings, they related to them, like in Mexican mural art. It wasn't elitist art. It was art that had a message. In the early times when we used to have these exhibitions in schools and municipality halls, you wouldn't imagine the number of people who used to come. They would go so close to the paintings to look and absorb and ask questions. It was a very special time, and necessary. Then New Visions started experimenting. Framed works started getting out of the frame, the materials changed, and the subject matter became a bit more abstract.

RC: Did that shift create tension between the New Vision artists and other Palestinian artists?

VT: I think it was looked at as a mutiny. But then the political scene changed a lot, and there was more exposure to the outside world. It was easier for younger artists to travel, study abroad and get involved in the international art scene. Eventually the League of Palestinian Artists dwindled and did have the same role as it had before. Artists still incorporate Palestinian-inspired themes. The last work I did was a big installation, Warriors Passed by Here [2019]. I started drawing landscapes on big, long Japanese paper. They were so beautiful. And I said, “This landscape also has been ruined by so many soldiers who have passed through, by the settlements, by the wall that's cutting through the fields, by the uprooting of trees, by Palestinians themselves building without any kind of proper planning.” And I made the helmets, representing the different civilizations by which Palestine was trespassed.

Vera Tamari, Sanctuary, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

RC: What’s the significance of the olive tree in your art? Do you want to talk about the series Olive Tree Women, 2009-2019? Some of their marks conjure hair, maybe pubic hair, and others make me think of hatchet marks and bandages.

VT: The olive tree was always a symbol that Palestinians used. It's all over the landscape. The olive tree was linked with the farmer and the rootedness of Palestinians. It's majestic and solid. Some are thousands of years old. They're called Roman trees and have very twisted trunks. Time has given each trunk a personality. I felt they were very sensual, too. The curves in the trunks. I always felt they might be the torsos of women. It's like these figures [in Dance] are dancing in an open space. It's lyrical. Other ones are not as light, [like] Bondage. Sanctuary is more like a body that's holding something precious in a warm way, and it becomes like a holy place. Toward Dawn is a lifting upwards. The names came afterwards. I loved working on [Olive Tree Women] because it was a new medium for me. It’s on fabric, and I used dyes and water watercolor and chalks to work on them. I stitched fabric on fabric. I made different layers to give transparency and volume to the works. They're quite big, about two meters long by 80 centimeters in width. They hang in a series on a piece of paper with Plexiglass on top.

I did another completely different [work about] olive trees, called Tale of the Tree [2002] during the incursion in Ramallah in 2002. There were people whose livelihood depended on the olive trees. Every day in the papers one would read about the destruction of olive trees. I was very affected by that. Army jeeps were going, there was a curfew, and it was all very intense. I started modeling little olive trees. It was therapeutic for me, and in my mind I kept saying, “For every olive tree that's being uprooted I'm going to make a clay olive tree.” In the end I made hundreds, 600 or 650, all [in] soft, colorful tones, like a reverie for the future of the olive trees. They were all on a plexiglass base. It’s one of my favorite artworks, frankly.

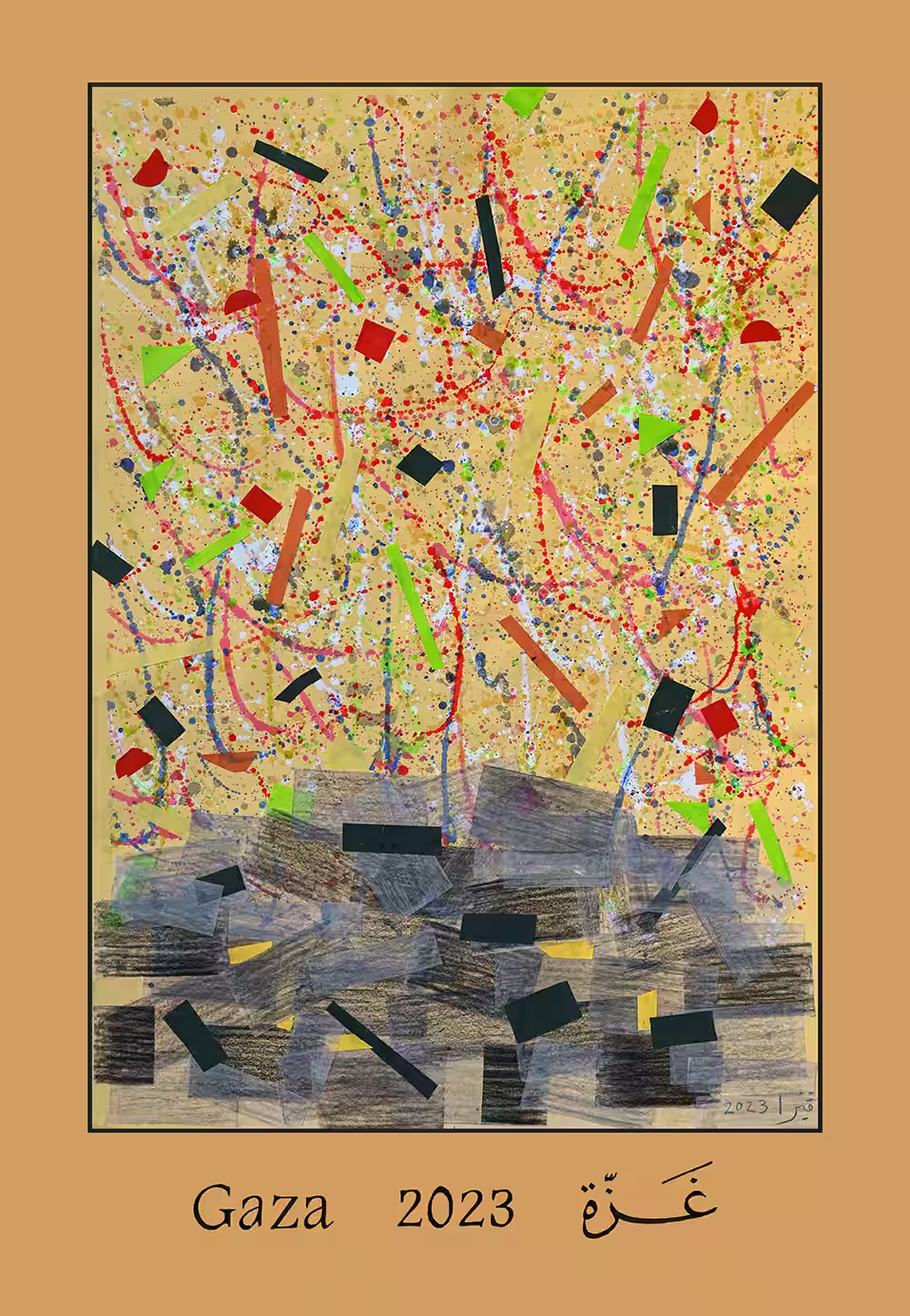

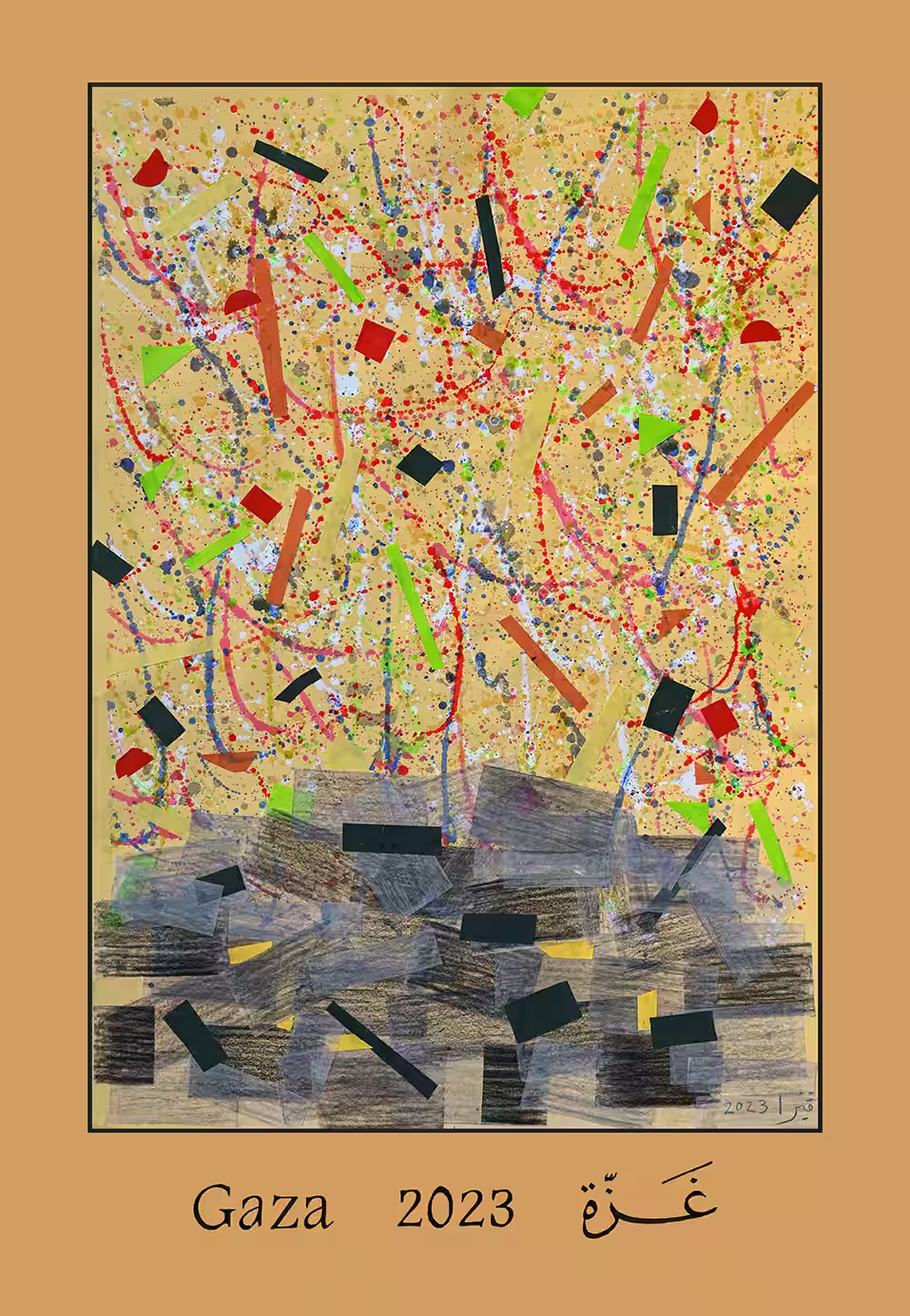

RC: I have to ask about a poster you made for the current group show “Posters for Gaza” at Zawyeh Gallery in Dubai.

VT: I never did a poster in my life. I couldn't even imagine an artwork that would really relate the feeling of what's going on in Gaza. It's too much. So I felt like expressing the destruction formally, in an abstract way. And also the light and hope. This combines both. It’s collage—tracing paper and watercolor. I didn't put the title to it. I intended in the beginning to put a little saying by [the poet] Mahmoud Darwish. It doesn’t translate well [to English]. But then I felt it was cliché.

RC: The bottom of the poster reminds me of so many things: ashes, rubble, a hole.

Vera Tamari, Gaza from the rubble soars life, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Zawyeh Gallery.

VT: Exactly. The accumulation of so much grayness. When you see the new landscape of Gaza, you see dust and people who are gray. The houses are gray, the streets are gray, the donkeys are gray. So the collage uses a lot of grays, but you never can give the feeling of the destruction. I don't know if I was successful or not.

RC: The bright colors at the top make me think of pamphlets, raining down. It also makes me think of bombs, and confetti—something weirdly celebratory.

VT: A friend of mine saw something totally different. She said, “Ah, these are the light spirits of the children who have died and gone to heaven.” Some people said, “Ah, these are the shelling.” It's interesting how different interpretations can come.