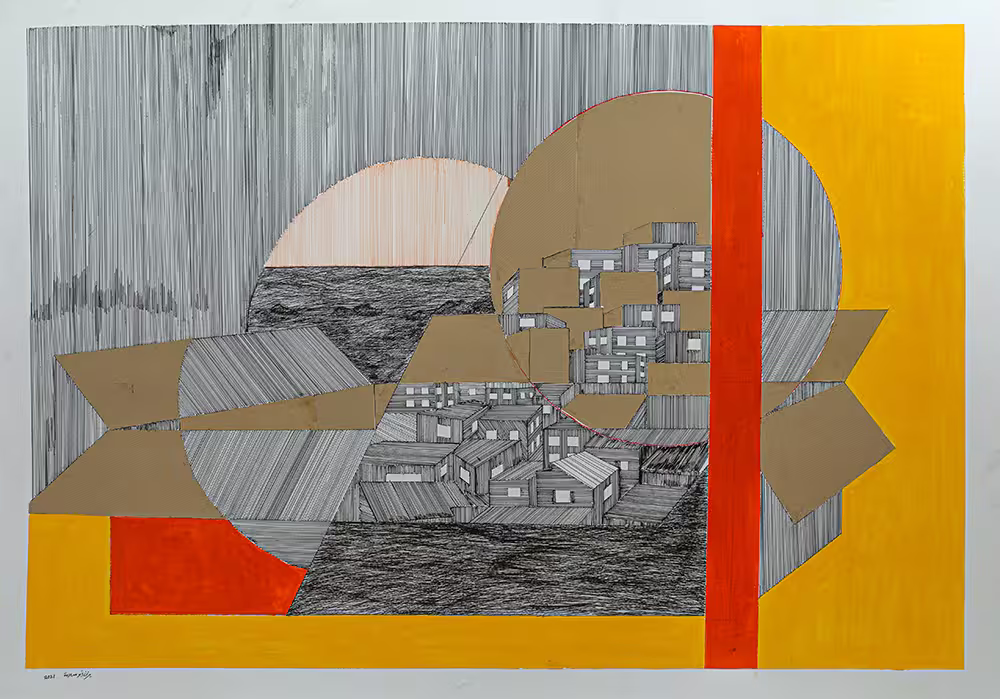

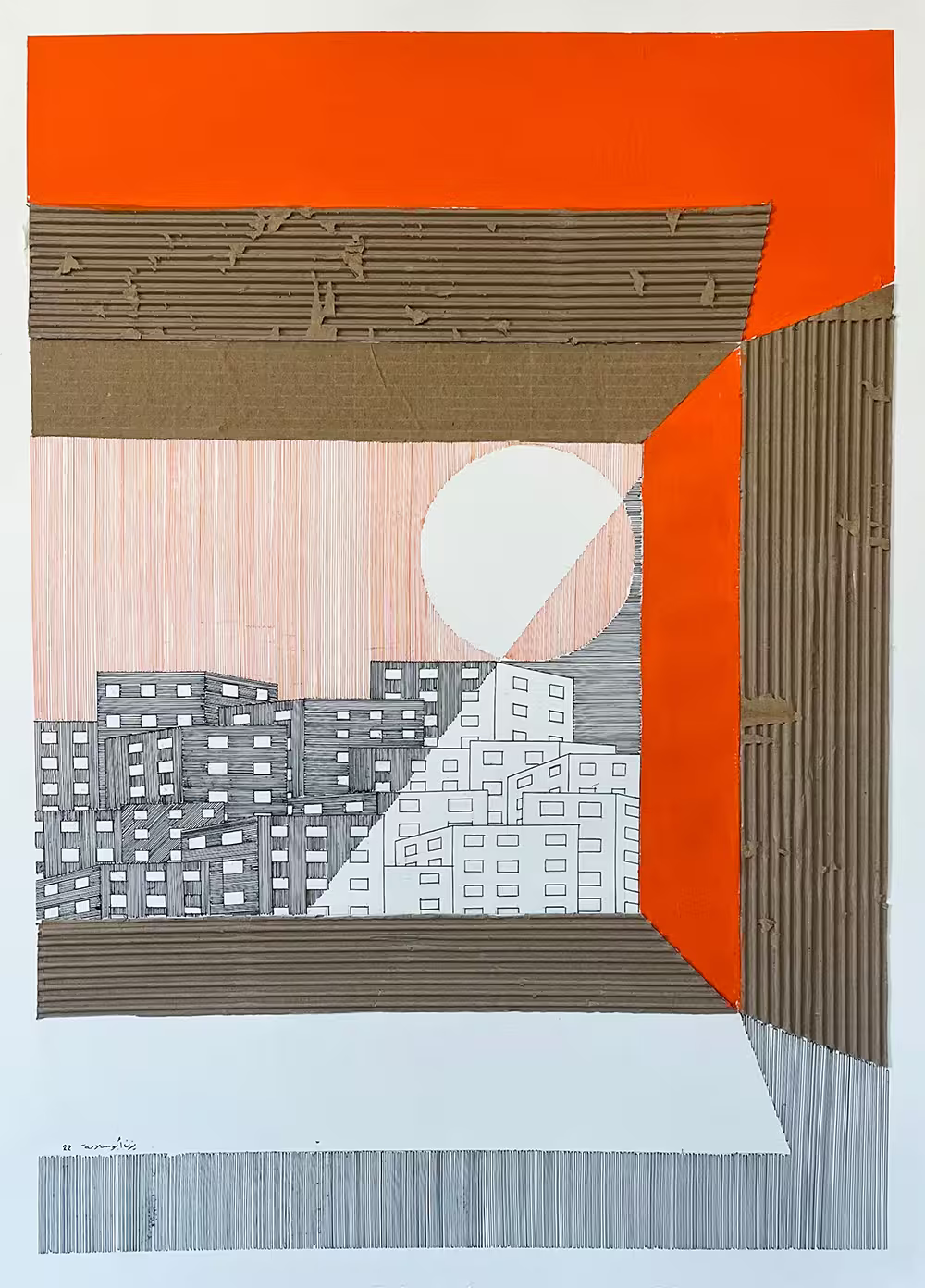

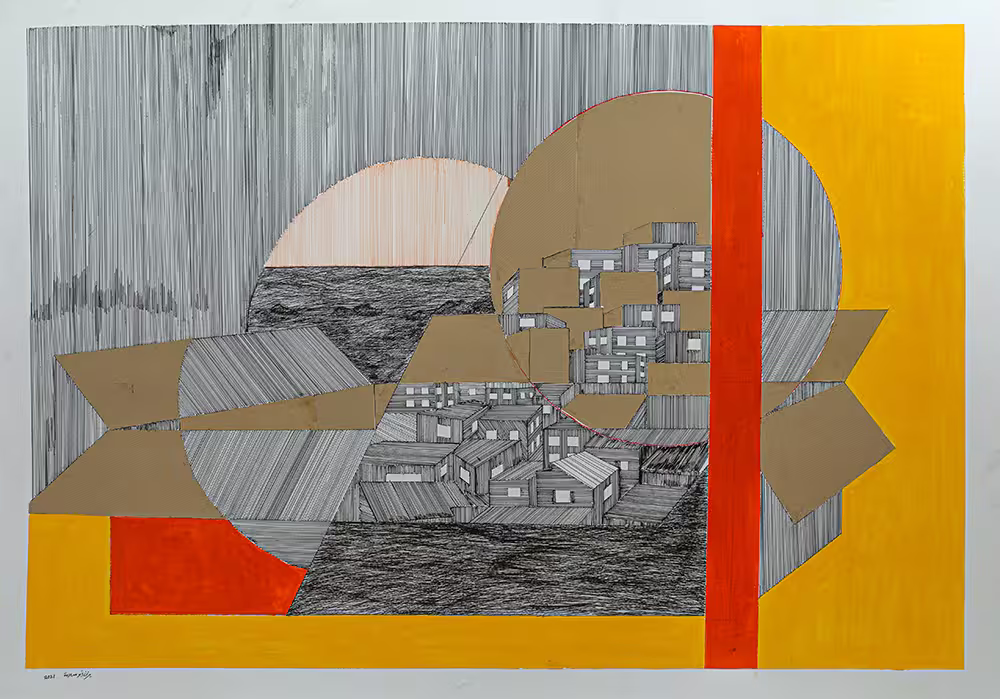

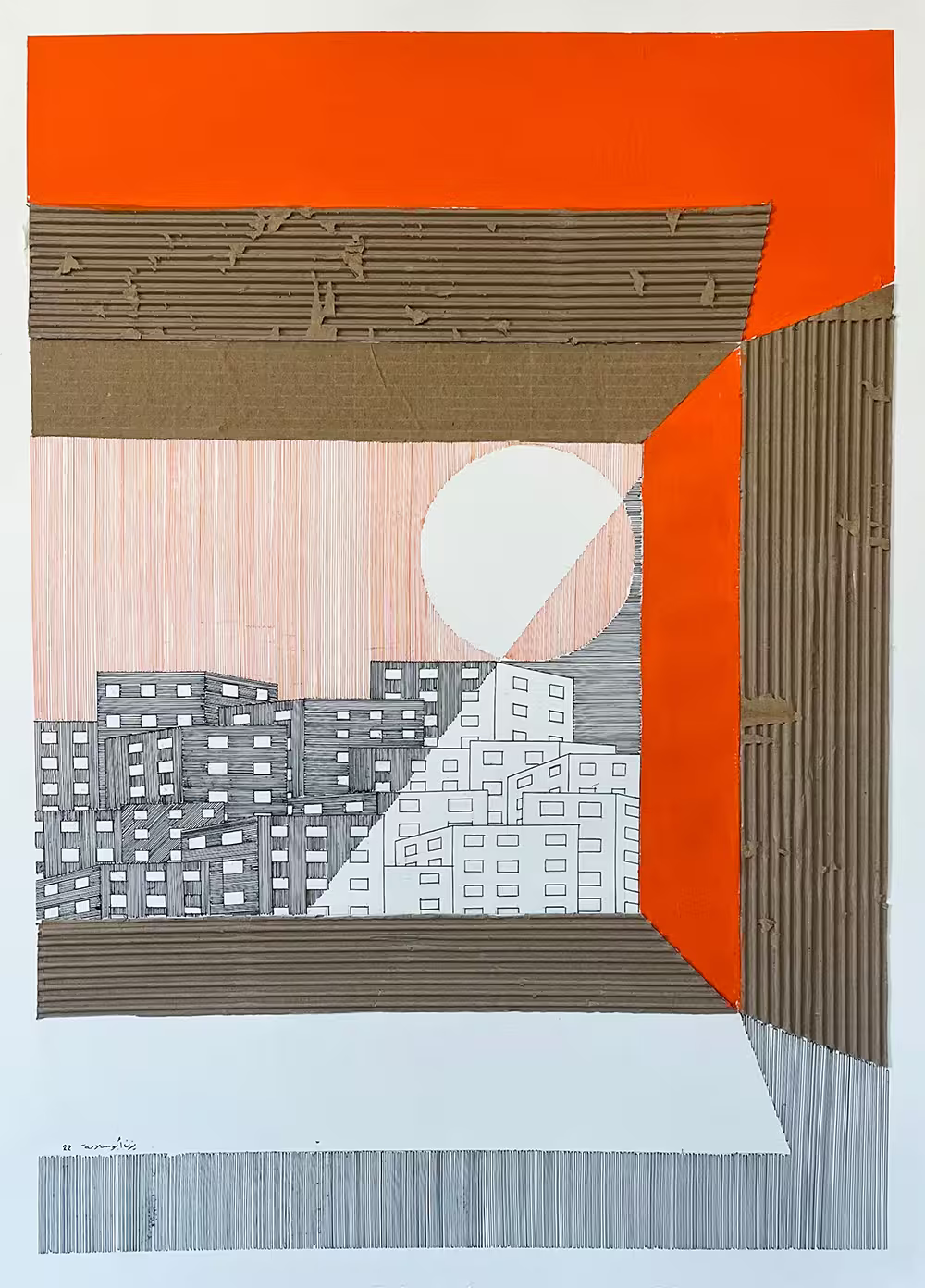

Bleak, transfixing, meditative: Such is the work of Yazan Abu Salameh, an artist living in the West Bank. Salameh depicts the landscape of Palestine with geometric abstraction that is heavily symbolic but largely free of iconography. The sun features prominently—usually as a deep orange orb, in whole or in fragments—as does the West Bank Wall. Interiors and exteriors mingle, making nature and human fabrication harder to distinguish. In Ramallah Blocks the Sun #4, 2023, he deploys the grid as a series of tall, tightly packed buildings. We look into them as if their roofs have been lifted and see inside, where shadow and light play across a pattern of repeated partition. For this and many other mixed-media works, the artist uses a fine-tipped pen and ruler to draw straight, densely packed ink lines, producing an effect he compares to a barcode. In Bethlehem, 2022, such lines are lighter, summoning the gray of concrete. The top of the West Bank Wall appears as a false horizon.

The son of a doctor and a schoolteacher, Salameh, 30, grew up in Bethlehem all but cut off from Jerusalem, where he was born. As a child he made art “like any child,” before studying fine arts at Dar Al-Kalima College in Bethlehem. “I found myself when I studied, not after and not before,” Salameh says. For a few years he worked at the Walled Off Hotel, Banksy’s controversial hotel-cum-gallery in the West Bank, before Covid forced the space to temporarily close. The pandemic afforded Salameh time to focus on his own practice, and in 2021 he was featured in the inaugural Ramallah Art Fair. Last summer, he moved from Bethlehem to Ramallah. When we spoke in January, he was in residence there at the Qattan Foundation and working, among other things, on a painting he began in 2021 called West Bank 2002, in reference to the year Israel began erecting the West Bank Wall. He declined to show it to me in its incomplete form but described it as personal, “inspired by my life.”

Salameh is one of 26 artists who contributed to “Posters for Gaza,” a group show currently on display at Zawyeh Gallery in Dubai. It aims to raise awareness of Gaza’s ongoing crisis, with sales of online reproductions benefiting the Palestine Red Crescent Society. When we spoke in January over Zoom, Salameh expressed ambivalence about the relevance of art to the current moment. “When I talk with you about art, what has art changed for those killed?” he asks. “It's not bad. It gives people hope and things to say and to think about it. But it's just a feeling.”

-by-YAS.avif)

Yazan Abu Salameh, Ramallah Blocks the Sun, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist and Zawyeh Gallery.

Rose Courteau: You mentioned that Bethlehem is quiet right now. Why is that?

Test Image Caption

Yazan Abu Salameh: It's a really religious place. The Nativity Church is there, and everybody came to it to pray. Now there are no tourists, because the border is closed. There is no life there. All the hotels are closed, and the restaurants. You can go to school and you can care for your family, and that's it. It's not like before this war. You cannot do your art [in Bethlehem]. It's hard to get resources, like colors. Ramallah is more open. They have a lot of resources here in Ramallah.

RC: Are your materials more limited because of what’s going on?

YAS: I buy a lot of materials to save, because I know there is a war. It's like [stockpiling] food, you know? [At] this moment, I am good; about the future, we don't know if we’re still alive.

RC: What are you working on right now?

YAS: I have this work, The Separation, 2024. It's my shadow at the doors. They separate the shadow at the doors, I mean the doors of the borders. You cannot have one identity. They give you two. You have two identities here.

RC: Who are the figures?

YAS: These are people who wait all the time at the borders to see us. I have a lot of friends inside [Israel]. But it's very hard to meet them, so I paint myself looking for them. The sun is two circles here. And at the same time it's cloudy. You cannot understand and you cannot see. It’s crazy to live in all the time. I don't want to say it's normal for us now. It's not normal.

RC: You seem really drawn to these geometric shapes. Where does that come from?

YAS: During the holidays and summer [when I was in college], I worked construction to get money. I took ideas from construction. I use the circle all the time to focus. The sun is the point where we start and where we end. We live in circles.

RC: You said in a previous interview that you are inspired by the idea that anything that you are thinking, someone else is also thinking. Are shared mindsets something that you consider a lot?

Yazan Abu Salameh, Gift Box #2, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist and Zawyeh Gallery.

Yazan Abu Salameh, Gift Box #3, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist and Zawyeh Gallery.

YAS: Yeah. Like Gift Box, 2024, is about U.N. boxes. Everybody touches the box, because we are refugees. I am a refugee. I am from the fourth generation. Organizations like the U.N. make people think about food and how to survive, not about rights. They take the land and they take the work, and they put the mind of refugees inside these boxes. Refugees think about these boxes all the time. They don't think about return. They work to just get food and money to survive, with the silence of these organizations.I trust my art because it’s not just about me. All the refugees catch boxes. It's a memory for everybody.

RC: What did you do when you worked at the Walled Off Hotel?

YAS: It's a long story. I worked with Banksy for three years. [Before working at the hotel] I didn't hear about him. I needed work. There's a gallery in the hotel, and I went to visit it every day. I did art and would sell it for the tourists. Then after one year, Banksy [gave me] approval to do his art. Like, he’d have the idea, but he gives his approval for me to finish it.

RC: Like a studio assistant?

YAS: Yes. From this experience, I got a lot of techniques, a lot of materials, and good money, and I shared my art there at the gallery. It was the beginning for me. I thank [Banksy]. But it's not what I need all the time, to work under somebody, under his hands, under his name. So I left in 2020.

RC: What are some of your favorite works that you made during the pandemic?

YAS: I did a project about Legos, Cemented Sky. It’s about the economy and the political effect you can see [in] the buildings [of the West Bank].

RC: Can you talk a little bit more about the materials?

YAS: I work with a lot of materials. I use materials to make it easy for the people to see connections. If I want to do something about the boxes, I use a carton. If I want to do something about the buildings and structures, I use concrete. I use Legos because it's something we used as children. It's a game. Now I understand the world, who has the money [and] can build. I don't want to talk about political things, but everything has a connection to the political.

Yazan Abu Salameh, Red Alert, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist and Zawyeh Gallery.

RC: Will you talk about what you made for “Posters for Gaza” at Zawyeh Gallery?

YAS: All Rights Reserved, 2023, is specifically for Gaza, but in general it's for Palestine. So I write in Arabic, “all the copyright,” but the human rights they talk about are not in Gaza or Palestine. The sun is the hope for peace and revolution. The boxes are the U.N. They put us in the boxes and then they bomb these boxes. I make it black comedy, and I use these colors because it's the Palestinian flag. I used cardboard, ink, and acrylic.

They Are Not Numbers, 2023 is acrylic, and I covered the sun with tape. The flowers are the martyred who are killed in this war. Lots of places are empty for new flowers. I repeat the same [line], “They are not numbers,” like short, fast news.

RC: Is it challenging to explain or translate your work to people who are not Palestinian?

YAS: No. People understand it.

.avif)

-by-YAS.avif)