It’s an overcast spring day in New York, but the sun is still perpetually shining into the Chelsea Hotel, memorialized in paintings by the late artist Ching Ho Cheng. It was here where he would once watch the sunlight dip through his window and catch its silhouette on the living room wall, tracing its form in his paintings. These slices of his life are preserved by his sister Sybao Cheng-Wilson, along with hundreds of other works, photos, and ephemera—a portion of which is on view this month at Bank NYC.

Today, Cheng-Wilson sits inside the same (now refurbished) building that her brother once lived and worked in throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s until his untimely death at the age of 42 in 1989 from AIDs-related complications. The artist’s work continues on in perfect harmony with the apartment: a selection is thoughtfully displayed on the walls, and hundreds of paintings are neatly filed away in the office.

“I made a promise to him to care for his work,” she says, even though her brother left her with no instructions about how to manage his estate upon his passing—so she taught herself how, learning more about his inner world as she delved deeper into his practice. “It's like talking to him,” she says.

Everyday, Cheng-Wilson looks toward her living room window and, for a moment, imagines she is seeing through Cheng’s eyes. At Bank NYC, the late artist’s varied untitled window works from the late ‘70s to the early ‘80s render such moments of contemplation in twilight-blue and sunset-amber. As the sky changes with the seasons, she traces its colors across his paintings. She watches the reflection of the window on the wall too, like a sundial. “And maybe once or twice—I don’t know why, but when the sun hits at the right time in the right season and I'm in the room—there'll be rainbows all over,” she says, recalling the first time she saw one and was awestruck. She reaches for a circular painting of a rainbow: “I always start with this little painting that Ching did early on.” Another work on the wall features the same motif with a butterfly emerging from it. “He was already thinking about transformation,” she says. “All his paintings are about life after death to put it simply.”

Born in Havana, Cuba to Chinese diplomats who were exiled during the Chinese Revolution of 1949, the siblings grew up in Queens and came of age during the Vietnam war. Cheng-Wilson remembers once in their youth overhearing her brother and his friends discussing their fears of the draft and the possibility of death. He avoided the military and instead ended up pursuing his life-long interest in painting at the Arts Students League and, later, the Cooper Union School of Art, where he immersed himself in Tibetan tantric art and Taoist teachings. “He loved these geometric shapes,” she tells me of his cosmic preoccupation. “I look them up, and they all have some meaning about the next realm and enlightenment.”

“He believed in another energy,” She says, leading me to a filing cabinet full of soft, prismatic images. Behind us is a painting of a pink-tiled shower, a match burning like a sailboat adrift at night, and light siloed by an entryway. Cheng's universe was both highly personal and spiritual. “I keep seeing it everywhere. I can't escape it,” he once said in an interview for The SoHo Weekly News. “It’s energy. I see it in a streetlight. I can see it in an oil slick on the road. I can see it in a peach pit.”

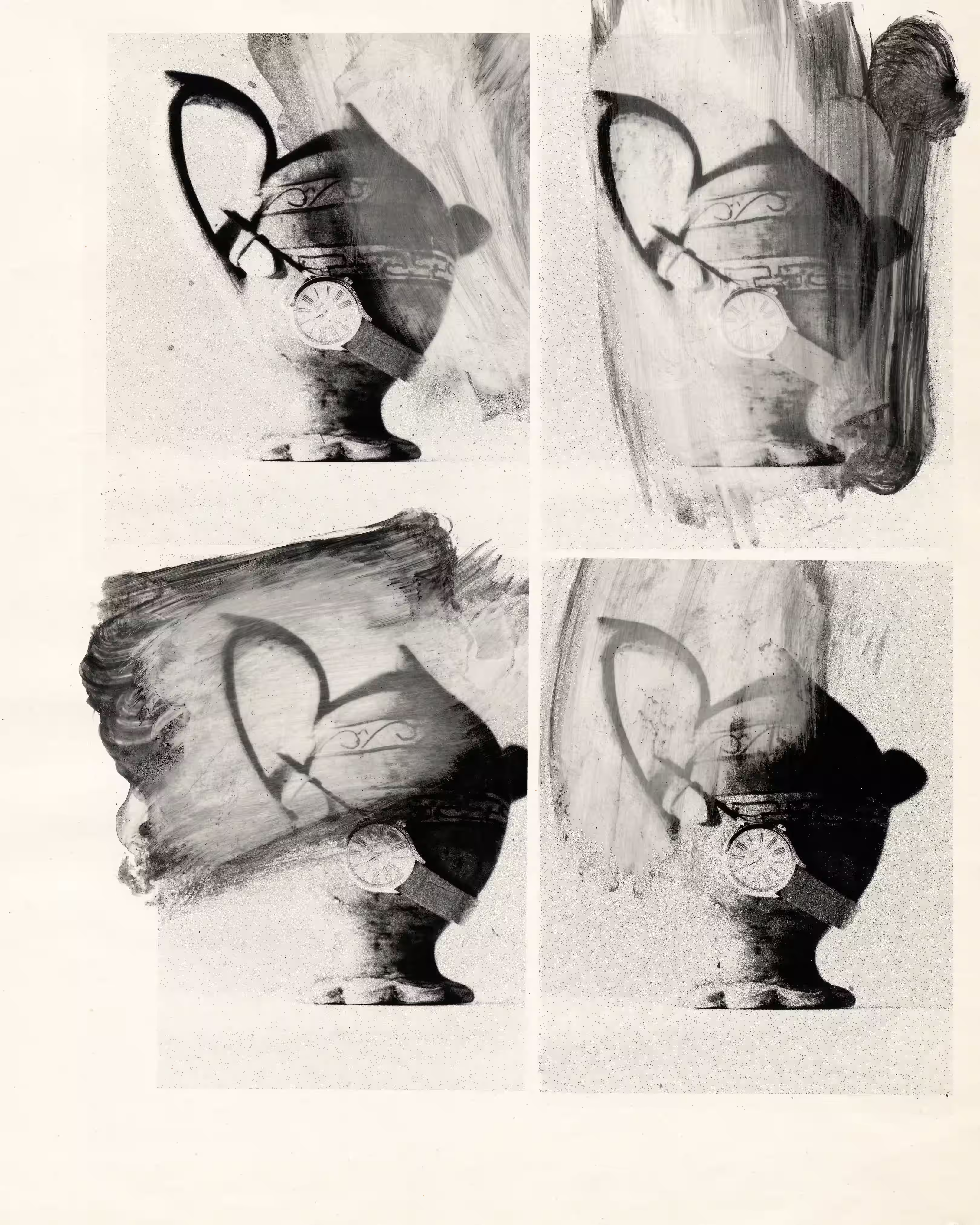

Throughout his practice, Cheng developed his own vocabulary only to reduce it to its purest form as if reaching at something ineffable. His work can be divided into four distinct periods that progressed closer and closer into minimalism. Kaleidoscopic illustrations gave way to pastel portraits of butterflies and a man with a fully tattooed face. Eventually, he shifted to detailed zoomed-in depictions of everyday objects. These objects receded into the background, like a small nail in the middle of a blue shadowed wall. Then they transformed into minimal works that reduced paper to a material rather than a blank slate—first torn paper and then textured, alchemical works, coated in rusted iron or copper.

His oeuvre followed a pilgrimage of simplicity that was snuffed out by fate before he could ever reach full absolution, before he could pare his vision down to some hard, compact truth, or to enlightenment. Or maybe rather than continue on a path of monk-like reduction, if his works were to have continued, they would have become more three-dimensional until they’d turn into sculptures.

A painting of a hand-written poem on torn paper hangs above his sister’s head, a collaborative piece with the late poet David Rattray. Old family photos are laid out on the table in front of her. She picks up an image of herself sitting on a rounded wicker armchair dressed in a pearly qipao, with Cheng cutting a stunning figure by her side in a black velvet Chinese tunic suit. Their hair in matching shoulder-length shags was his idea. “When I look back now, I see that my brother has had a hand in my entire life,” she says with a laugh. She recalls how he would often give her a painting on her birthday, as if he were in a sense preparing her for the monumental handoff that came far too soon.

“Even from when I was little, he took care of me because our parents were out working, and then he got me into art school in Manhattan and I would spend weekends in the city hanging out with him. And now, he's gone and I’m still here,” she says as she gestures at the room. “I do feel a connection with Ching in my dreams; things pop in my head,” she reflects, trailing off into thought. “I don't think he would think that I could do this this well.”

And though she is youthful and striking—her long, black hair worn half up with face-framing fringe bangs, thick eyeliner—Cheng-Wilson notes that she will eventually have to hand off the estate to someone else. “I’m not getting any younger,” she says. But in the meantime, its full speed ahead, and the artist is finally getting his dues as a pivotal figure in New York’s post-war art scene, despite being marginalized for his identity as both gay and first-generation Chinese.

This fall, Cheng will be included in the Whitney Museum’s group survey “Sixties Surreal,” followed by his first retrospective, which will travel, beginning at the Addison Gallery of American Art in 2027 and marking his first institutional show. “When your will is strong, you can do anything because I never would have dreamed that I could manage this,” she muses. “It's taken a long time, but it's really starting to happen.”

"Ching Ho Cheng: Tracing Infinity" is on view until June 14 at Bank NYC at 127 Elizabeth Street, New York, NY 10013.

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

.webp)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpeg)

.avif)

_11%20x%2014%20inches%20(2).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%2001%20hr.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

3_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)