When Takashi Murakami was growing up in 1960s Japan, the shadow of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki loomed over the collective cultural consciousness, ripe with diffuse trauma. His earliest sense of self reified in this environment. At the same time, anime exploded alongside the ubiquity of household T.V.s., and the artist would pick up on veiled (or not so much veiled) references to World War II. ”It suddenly became very realistic,” he says of the frequent allusions to the war incorporated into the animations. “As a child, you can understand that adults really wanted to create a serious message… For my generation, that became the blood and meat of our being.”

Since the 1990s, Murakami’s oeuvre has been punctuated with his signature cartoon motifs repressing something beneath their technicolor grins. Throngs of smiling flowers imply just a twinge of hysteria. Characters have multi-colored-bullseyes for pupils; others, fanatically bared sets of pointed teeth. Extra eyes peer from the same face, often with personalities of their own: long-lashed and cute, drooping as if drugged out, or sometimes, conversely, psychotically alert.

Though the artist is widely known in mainstream pop culture for his high-profile collaborations, a survey at the Cleveland Museum of Art, “Takashi Murakami: Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow,” leans into this darker reading of his work. The titular piece, In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow, 2014, is an 82-foot long painting he made in response to the cataclysmic 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. Its panels explode with color and swooshing textures. Out of this phantasmagorical din emerge twisted figures, dragons, and skulls engorged with smaller skulls. The contradiction between superficial imagery and subject matter demands that the viewer digest the full impact in double and triple takes; sugary and silly fall away into mutations, memento mori, pain, horror. The fairground is a killing field.

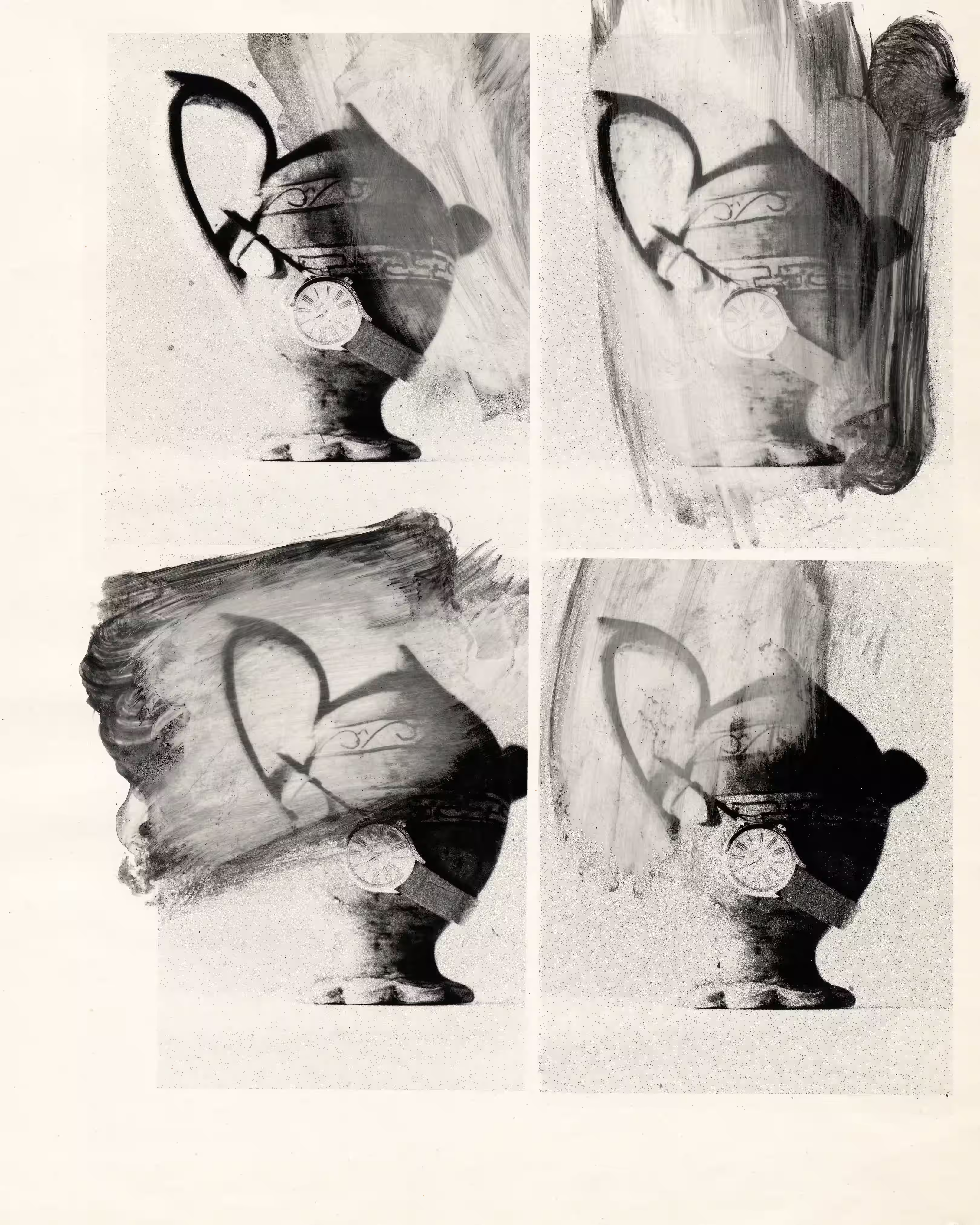

Opposite this in the exhibition sits a series of vases that Murakami fashioned as copies of those that existed in the Japanese-ceramics collection of the late artist Kitaōji Rosanjin. Echoing the theme of loss from natural disasters, Rosanjin saw much of his inventory destroyed in the 1923 Tokyo earthquake; he then set about making replicas of the shattered pieces. “In this spirit, Murakami is making a copy of a copy, speaking to not only that story of loss and rebirth but also about both Japanese and Western thinking about reproduction and what copies retain and lose in the act of their creation,” says curator Ed Schad.

A painting from 2022, Unfamiliar People, taps into a plane of surreal, interpersonal unease, namely from Murakami’s observations during the depths of Covid, as people’s increasingly vicious and conspiratorial online commentary clashed with real-life impressions. The figures are bizarre, skewed, almost melting. Wild-eyed, they slouch or strike unnatural poses. “Back then, social media was a window to communicate with other people; anger was enhanced, and fake information was spreading. People felt like there was nothing they could believe or rely on,” says Murakami of channeling the mood of the pandemic. “I think the artist’s job is to purge out that type of feeling.”

While the exhibition originated at The Broad in 2022, the new showing at Cleveland adds a site-specific installation in the form of a massive, functional Japanese temple in the lobby atrium that recreates the octagonal Yumedono (meaning “Dream Hall”) at the Hōryūji Temple in Nara Prefecture. For this, the artist sought out the set designers behind the historical drama series Shogun (2024–ongoing), which takes place in Japan in the year 1600, and of which Murakami was an instant fan. “I felt [the show] was trying to do something similar to what I have always been trying to do, to convey Japanese culture to the outside audience,” he says.

Back in 2014, Murakami’s solo show at Gagosian unveiled a conceptual predecessor to the Yumedono recreation, in the form of an archway replicating the 10th-century entry gate to Heian-kyo (now Kyoto), titled Bakuramon. The artist commented at the time that the sculpture addresses a "recurring theme of misinterpretation in my work.” Now, he reflects, “That hasn’t fundamentally changed”—especially in the intangible that has been lost in translation across his career-long endeavor to interpret the ethos of post-war Japan for a Western audience. In making the gate in 2014, he strove to replicate it down to near-exact materials, such as wood that had been drying for 40 years. For the Yumedono temple at the Cleveland Museum of Art, he allowed himself to take a more relaxed approach, with the results more akin to a film set. “It’s built with metal structure and plywood; it’s very far from the real thing,” Murakami explains. “In a way, that means I’m more confident about this misinterpretation concept.”

This dynamic, with its assumption of lapses in communication when it comes to socioculturally charged iconography, also subtly surfaces in Murakami’s smiling flowers. Before being franchised with what he describes as a more “simple, friendly smile” across various commercial goods, these originally featured in his paintings sporting gaping-mouthed, glazed-over expressions. Of these, he says: “I thought it would be a good way to cut off communication… Because when you first meet strangers and say, ‘Hello,’ maybe you just put on a smile for formality. But then you’re wondering, Why are they smiling?”

After our conversation, there is a press conference in front of another monumental painting, 100 Arhats, 2013, the term arhat referring to the figures who’ve reached enlightenment in Buddhism. I watch as Murakami, not yet visible to the crowd, puts on a stuffed plushy hat in the shape of a smiling flower. Suddenly, he is animated. He grins and puts his hands in the air, and the audience cheers fanatically as he walks into view.

“Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow” is on view until September 7, 2025, at the Cleveland Museum of Art, 11150 East Boulevard, Cleveland, Ohio, 44106.

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

_result_result.avif)

.avif)

.webp)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpeg)

.avif)

_11%20x%2014%20inches%20(2).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.avif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%2001%20hr.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

3_result.avif)

_result.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result_result.avif)

-min_result.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

_result.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

.jpg)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)